I am discontinuing the food but was wondering if I need to wait a certain amount of time before starting her back on methimazole?

My Response:

I've heard the same story from many cat owners and veterinarians. The y/d just doesn't appear to look and taste very appetizing to many cats (the food certainly looks pretty gross to me, but I must admit — I haven't tasted it!).

If the cat's serum T4 value is still high now, I'd switch the cat to a good diet (higher in protein, lower in carbs) that she wants to eat and start methimazole now.

- A 7-year old Siamese could live a very long time, possibly another 15 years! I'd talk to the owners about the following facts when you discuss how to treat the cat's hyperthyroidism (1-5):

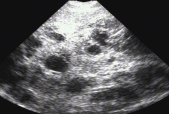

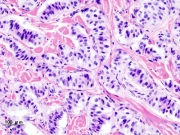

- This cat, like all hyperthyroid cats, has a thyroid tumor

- The thyroid tumor and hyperthyroidism will never go into spontaneous remission

- The thyroid tumor will continue to grow larger with time

- In some cats treated long term medically, the benign tumor will transform into a malignant thyroid carcinoma. In my studies, the incidence of thyroid carcinoma is above 20% in cats treated medically for longer than 4 years (6).

If this was my own cat, I'd either do surgery or radioiodine to cure the cat's hyperthyroidism rather than trying to manage it with an iodine deficient diet (Hill's y/d) or methimazole for the rest of her life (1-5,7,8). She is already suffering from a severe case of hyperthyroidism, which will only worsen with time.

In the long run, a definitive treatment would be the wisest (and most cost effective) means of treating this relatively young cat.

References & Suggested Reading:

- Baral R, Peterson ME. Thyroid gland disorders. In: Little, S.E. (ed), The Cat: Clinical Medicine and Management. Philadelphia, Elsevier Saunders 2012; 571-592.

- Peterson ME: Hyperthyroidism, In: Ettinger SJ, Feldman EC (eds): Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine: Diseases of the Dog and Cat (Fifth Edition). Philadelphia, WB Saunders Co. 2000; pp 1400-1419.

- Peterson ME: Hyperthyroidism in cats. In: Melian C (ed): Manual de Endocrinología en Pequeños Animales (Manual of Small Animal Endocrinology). Multimedica, Barcelona, Spain, 2008, pp 127-168.

- Mooney CT, Peterson ME: Feline hyperthyroidism, In: Mooney C.T., Peterson M.E. (eds), Manual of Canine and Feline Endocrinology (Fourth Ed), Quedgeley, Gloucester, British Small Animal Veterinary Association, 2012; in press.

- Peterson ME: Hyperthyroidism in cats, In: Rand, J (ed), Clinical Endocrinology of Companion Animals. New York, Wiley-Blackwell, 2012; in press.

- Peterson ME, Broome MR. Thyroid scintigraphic findings in 917 cats with hyperthryoidism. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 2012; in press.

- Peterson ME: Radioiodine treatment for hyperthyroidism. Clinical Techniques in Small Animal Practice 2006;21:34-39.

- Peterson ME: Radioiodine for hyperthyroidism. In: Bonagura JD, Twedt DC (eds): Current Veterinary Therapy XIV. Philadelphia, Saunders Elsevier, 2008, pp 180-184.

have recently switched one of my canine diabetic patients from

have recently switched one of my canine diabetic patients from