I read your recent post regarding Addison's disease and I'm writing to see if you could clear up (or add to the debate) a discussion that we are having at our hospital. I am a second-year medicine resident and our medical staff is having a debate about what is considered a normal vs. an abnormal cortisol response to ACTH stimulation and what exactly is "atypical" Addison's disease.

I read your recent post regarding Addison's disease and I'm writing to see if you could clear up (or add to the debate) a discussion that we are having at our hospital. I am a second-year medicine resident and our medical staff is having a debate about what is considered a normal vs. an abnormal cortisol response to ACTH stimulation and what exactly is "atypical" Addison's disease.

For example, what about dogs that have chronic gastrointestinal (GI) signs that have not yet been been diagnosed but a flat cortisol response to ACTH stimulation is found? If we perform an ACTH stimulation test on these dogs, many will have a basal cortisol level well within reference range limits (e.g., 2 to 4 µg/dl) but the post-ACTH stimulated cortisol concentration will not rise to levels 3-5 times higher than the basal cortisol concentration. Some of these dogs will have ACTH-stimulated cortisol concentrations that are below the post-ACTH reference range (e.g., in the range of only 3-6 µg/dl). Is this atypical Addison's disease?

What do you do in these cases? Look for other causes of the GI signs? And if no other cause found supplement with steroids? Should we just repeat the ACTH stimulation test down the line?

Thank you for your time!

My Response:

First of all, you must remember that the blog post on Addison's disease you are referring to was written primarily for dog owners, not veterinarians. I was trying to be clear, which is difficult when we are discussing a topic that could include typical, atypical, or secondary adrenal insufficiency.

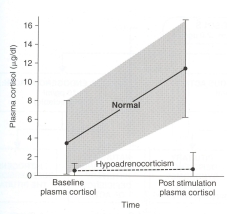

Almost all dogs with primary hypoadrenocorticism (typical Addison's disease) and near complete destruction of the adrenal cortex will have subnormal basal and ACTH-stimulated serum cortisol concentrations (<1 μg/dl).

Dogs with secondary hypoadrenocorticism (pituitary ACTH deficiency) have low to low-normal basal cortisol values that may rise very slightly to ACTH stimulation, but the cortisol response is very blunted (post-ACTH values generally < 3 µg/dl). This has all been published (1-3), and I don't think anyone would strongly disagree with those guidelines.

The problem with "atypical" Addison's disease is that, at least most of the time, the dogs have never been worked up properly to differentiate primary from secondary hypoadrenocorticism. Most would define "atypical" Addison's simply as glucocorticoid-deficient hypoadrenocorticism, but that is really being quite simplistic and does not help guide what replacement therapy may be needed or predict prognosis.

In other words, if that "atypical" dog has primary Addison's disease with normal electrolytes, it is very possible or even likely that mineralocorticoid replacement will be needed. On the other hand, it a dog has secondary hypoadrenocorticism, mineralocorticoid replacement will never be needed, but pituitary imaging (CT or MRI scan) might be indicated to exclude a pituitary mass.

The easiest way to differentiate primary from secondary hypoadrenocorticism, of course, would be to measure plasma ACTH concentration, but that must be done before any glucocorticoids have been administered (or after 1-2 weeks off all steroids).

If the plasma ACTH value is low (generally < 20 pg/ml) in a dog with a severely blunted serum cortisol response to ACTH stimulation, that would be diagnostic for secondary hypoadrenocorticism (1-4). As you know, ACTH deficiency is rare and is most commonly associated with a pituitary tumor (3). By far the most common cause is iatrogenic secondary hypoadrenocorticism resulting from glucocorticoid administration. So it's extremely important in dogs with "atypical" Addison's disease to go back in the history and make sure that they haven't received any steroid in the last few weeks to even months.

If the plasma ACTH value is high (generally >250 pg/ml) with a severely blunted serum cortisol response to ACTH stimulation, that would be diagnostic for primary hypoadrenocorticism (1-4). If the serum electrolytes are normal, that could be called "atypical" Addison's disease. Some of these dogs will certainly go on to develop serum electrolyte changes, whereas others never seem to do so. I suspect that these latter dogs do not actually have adrenal destruction, but may have an ACTH receptor defect where circulating ACTH values are high but the adrenal gland doesn't bind the ACTH so it cannot act to stimulate cortisol secretion. Again, the best way to distinguish secondary from primary hypoadrenocorticism in these dogs is to measure plasma ACTH before any glucocorticoids are administered (or off all glucocorticoids for at least 1-2 weeks).

But let me get back to your original question about the dogs that have chronic GI signs and whose ACTH stimulation test results reveal a normal (or low) basal cortisol with a post-ACTH cortisol values that is blunted, rising to only 3-6 µg/dl. This is certainly not a "normal" response, abut it's very difficult for me to explain why these dogs would have any signs when these circulating cortisol values are within or slightly above the normal basal range. If this was a dog on mitotane or trilotane, for example, we would be very pleased with those serum cortisol results and would not be worried about hypoadrenocorticism (5-7).

In my experience, most of these dogs have a history of being treated with glucocorticoids, which could lead to secondary (iatrogenic) hypoadrenocorticism. Again, if you would measure a plasma ACTH concentration in these dogs, the values should be low-normal if they do indeed have secondary ACTH deficiency. If there is now history of glucocorticoid use, I would certainly repeat basal or ACTH-stimulated cortisol values in 2-4 weeks, but most of these dogs do not end up having primary adrenal disease.

Now that's not to say that they don't need steroid supplementation, but not for "atypical" adrenal disease.

References:

1. Peterson ME, Kintzer PP, Kass PH. Pretreatment clinical and laboratory findings in dogs with hypoadrenocorticism: 225 cases (1979-1993). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1996;208:85-91.

2. Kintzer PP, Peterson ME. Primary and secondary canine hypoadrenocorticism. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 1997;27:349-357.

3. Feldman EC, Nelson RW. Canine and Feline Endocrinology and Reproduction.Third Edition. Saunders, 2003.

4. Peterson ME, Orth DN, Halmi NS, et al. Plasma immunoreactive proopiomelanocortin peptides and cortisol in normal dogs and dogs with Addison's disease and Cushing's syndrome: basal concentrations. Endocrinology 1986; 119: 720-730.

5. Kintzer PP, Peterson ME. Mitotane (o,p'-DDD) treatment of 200 dogs with pituitary-dependent hyperadrenocorticism. J Vet Intern Med 1991;5:182-190.

6. Peterson ME, Kintzer PP. Medical treatment of pituitary-dependent hyperadrenocorticism. Mitotane. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 1997;27:255-272.

7. Ramsey IK. Trilostane in dogs. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2010;40:269-283.

Źródło: endocrinevet.blogspot.com

© 2024 © Vetco 2015. Wdrożenie: Pracownia Synergii